You didn’t come this far to stop

Japanese Fighters and Allied Struggles in Malaya

Episode 25: Japanese Fighters and Allied Struggles in Malaya

As the Japanese forces advanced through Malaya in 1941, their air superiority quickly became evident. The most prominent Japanese fighters during this campaign were the Nakajima Ki-27 "Nate," Mitsubishi A6M Zero, and the Mitsubishi Ki-43 "Oscar." While these aircraft varied in design and purpose, they shared a critical advantage over Allied aircraft: superior maneuverability and experienced pilots. This episode delves into the Japanese fighter presence in Malaya, the comparison between British and Japanese bombers, and the critical training gap that impacted Allied air operations

WW2 HISTORYDESCENT INTO HELLIN THEIR FOOTSTEPS BLOG

Toursofwar.com

8/7/20246 min read

The Most Numerous Japanese Fighter

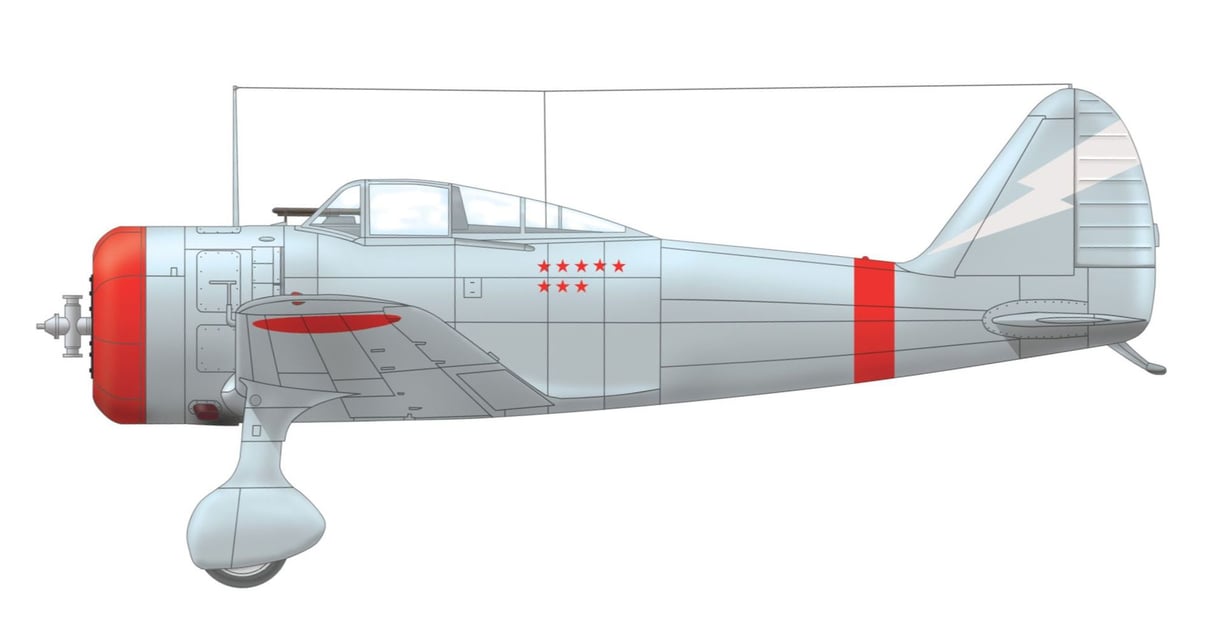

The Nakajima Ki-27 Nate

The Nakajima Ki-27, code-named "Nate" by the Allies, was the most frequently deployed Japanese Army fighter in the Malayan campaign. Though it was slower and more lightly armed than other Japanese aircraft, the Nate's strength lay in its incredible maneuverability. The aircraft's agility, combined with the superior training of Japanese pilots, made it a formidable adversary for the Allied fighters, especially the Brewster Buffalo, which struggled to keep up with the nimble Japanese planes.

A Dominating Presence

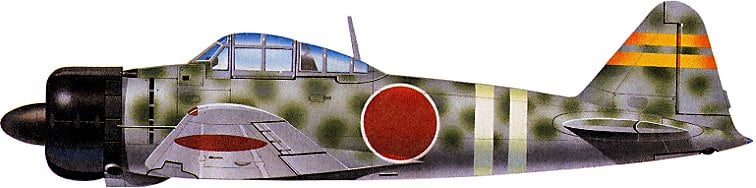

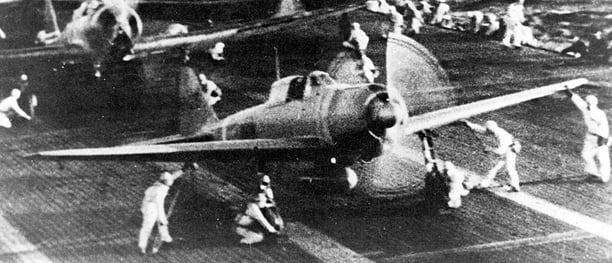

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero

While the Ki-27 Nate was the most numerous fighter, it was the Mitsubishi A6M Zero that captured the imagination of the Japanese public and earned the respect of the British. The Zero combined incredible agility with superior range, a high top speed, a rapid climb rate, and formidable armament for the time. The Zero was the supreme fighter in the Far East during the early stages of the Pacific War, capable of outmaneuvering and outgunning most Allied aircraft.

Christopher Shores and Brian Cull, in their book Bloody Shambles, described the Zero as having "almost unbelievable agility" and an unmatched climb rate. The Zero’s impressive combat performance helped solidify its reputation as one of the most feared aircraft of the early war years.

Did You Know?

The Nakajima Ki-27 Nate was the most numerous Japanese Army fighter during the Malayan campaign, despite being slower and less heavily armed than its counterparts.

Often Confused with the Zero

The Mitsubishi Ki-43 Oscar

Another important fighter in the Japanese arsenal was the Mitsubishi Ki-43, code-named "Oscar" by the Allies. Though often mistaken for the Zero, the Oscar was an Army fighter that also performed admirably during the fighting in Malaya. Like the Zero, the Oscar had excellent maneuverability, though it was slightly less capable in terms of speed and range.

In their analysis of Japanese fighters, Shores and Cull highlight that the Japanese superiority lay not in speed or altitude, but in the lightweight construction of their aircraft. This gave them better maneuverability, higher climb rates, and faster acceleration, which were critical in the close-quarters dogfights over Malaya.

Four squadrons of Brewster Buffalo fighters were deployed by the RAF and RAAF for daylight operations against Japanese fighters. Unfortunately, the Buffalo was no match for the agile Japanese planes. With its poor maneuverability and mechanical issues in the tropical climate, the Buffalo was often outclassed by the Japanese Nates, Zeros, and Oscars. The Buffalo pilots fought valiantly, but the aircraft's limitations were a significant handicap in combat.

Additionally, a squadron of Bristol Blenheim Mk I medium bombers, converted for use as night fighters, suffered from poor armament and antiquated design. These aircraft were not equipped to challenge the more modern Japanese planes, and their outdated bomb load and inadequate bombing accuracy further hampered their effectiveness.

Allied Fighters

The Brewster Buffalo's Struggles

The British relied on two squadrons of Blenheim Mk I light bombers and two reconnaissance squadrons equipped with Hudson bombers. The Blenheims, outdated and underpowered, were not formidable opponents for the Japanese aircraft. The Hudsons, on the other hand, were equipped with five machine guns and had a respectable bomb load, but both bomber squadrons were required to serve dual roles as reconnaissance and bombing units. This dual-purpose requirement limited the effectiveness of both their training and operations.

Furthermore, the British also deployed two squadrons of Vickers Vildebeest torpedo bombers. These biplanes, deemed obsolete by the RAF in 1940, were due for replacement but continued to operate in the region due to a lack of available modern aircraft.

Blenheim Mk I light bomber

Comparison of Japanese and British Bombers

Perhaps the most decisive factor in the air campaign was the experience and training of Japanese pilots. According to Douglas Gillison in Royal Australian Air Force 1939-1942, by December 7, 1941, approximately 6,000 Japanese pilots had graduated from training units, with 3,500 assigned to the Navy and the remainder to the Army. About 50% of the Army pilots had combat experience, either in China or during border skirmishes with Soviet forces. Additionally, 10% of the land-based Navy pilots had combat experience in China, and around 600 of the top Navy pilots were assigned to carrier units.

Japanese pilots received extensive training, with approximately 300 hours of instruction before joining tactical units. The average front-line Japanese pilot in 1941 had about 600 flight hours, while those in carrier groups averaged more than 800 hours.

Japanese Pilots

The Critical Component of Air Superiority

Did You Know?

Japanese Navy pilots averaged over 800 flight hours, compared to many Allied pilots in Malaya who were still undergoing conversion training or had far less combat experience.

In contrast, Allied pilots were significantly underprepared for the challenges of air combat. By late 1941, Australian pilots comprised about 25% of the total squadron strength in Singapore and Malaya. However, many of these pilots were still undergoing conversion training for the Brewster Buffalo. In September 1941, No. 21 Squadron of the RAAF was still converting to the Buffalo, and its most experienced pilots were being transferred to other units for training purposes.

To address the lack of operationally ready pilots, a temporary Advanced Flying Training Unit was established in Kuala Lumpur to train newly arrived Australian and New Zealand pilots. However, it took over four months of additional training before these airmen were considered ready for combat. This delay left the Allies with an inadequate number of experienced pilots to meet the immediate threat.

The challenges were compounded when No. 21 Squadron was re-tasked from general reconnaissance to fighter and army cooperation roles, requiring pilots to adapt quickly to new combat conditions. Many of these pilots had not been selected as fighter pilots and struggled to adjust to the new demands.

Allied Pilots

Inexperienced and Undertrained

Conclusion

The Japanese Air Advantage

The combination of superior Japanese aircraft, like the Zero and Oscar, and the extensive experience of Japanese pilots, gave the Imperial Japanese forces a decisive air superiority in the Malayan campaign. Allied forces, including the RAF, RAAF, and RNZAF, were hampered by outdated aircraft like the Buffalo and Blenheim, as well as insufficient pilot training and experience.

As the campaign progressed, the gulf in performance between Japanese and Allied air units became more apparent, leading to devastating losses for the British and their allies. The Japanese pilots' training, tactical experience, and aircraft maneuverability all contributed to their dominance in the skies over Malaya.

How You Can Help

Donations and Sponsorships: We are seeking corporate sponsorships and donations to fund ongoing restoration projects and educational programs. Your support can make a significant difference in maintaining the quality and impact of the museum.

Volunteer Opportunities: If you have expertise or time to offer, consider volunteering with us. There are many ways to get involved, from artifact restoration to educational outreach.

Spreading the Word: Share this blog and our mission with your network. The more people who know about the JEATH War Museum and its significance, the greater the impact we can achieve together.

The St Andrews Research Team is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Thai-Burma Railway and the memories of those who suffered. We need your support to continue our work. There are several ways you can help:

Join the Cause!

If you or someone you know is interested in supporting this cause, please get in touch.

This is a chance to be part of something truly meaningful and impactful.

Together, We Can Make a Difference!

This is a veteran-run project, and we need your help to make it happen. Stand with us in honoring the legacy of the POWs and ensuring their stories are never forgotten.