You didn’t come this far to stop

The Breakdown of Singapore’s Defense

Episode 28: The Breakdown of Singapore’s Defense

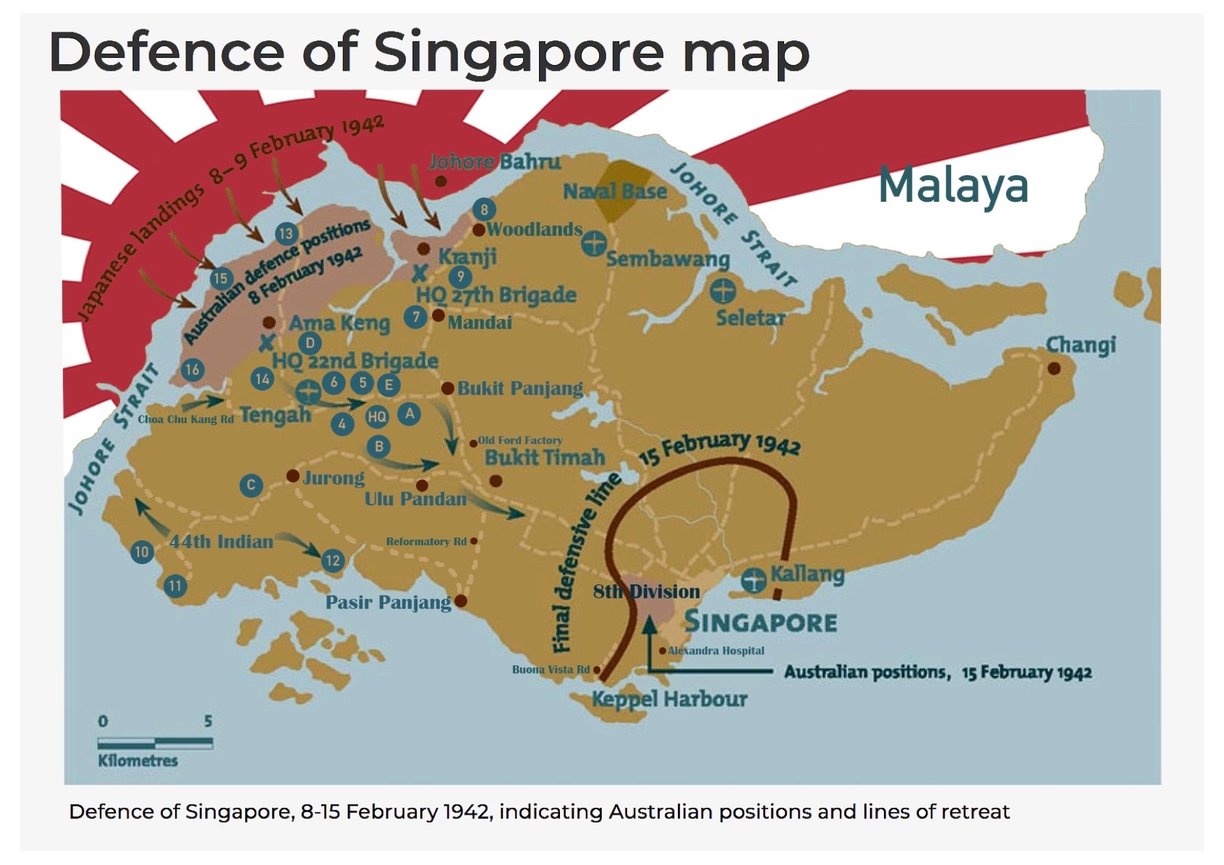

As the Japanese threat loomed larger over Singapore, it became clear that the city's defenses were not just ill-prepared but fragmented by internal conflicts and poor strategic decisions. While on paper, Singapore seemed like a formidable fortress, closer inspection revealed that flawed airfield defenses, lack of coordination, and weak leadership were leading to its unraveling. In this episode, we’ll explore how the animosity between key leaders, the under-defended airfields, and the reliance on outdated defense principles weakened Singapore’s ability to resist the inevitable Japanese invasion.

WW2 HISTORYDESCENT INTO HELLIN THEIR FOOTSTEPS BLOG

Toursofwar.com

8/10/20245 min read

Bond vs. Badminton

Internal Command Conflicts

One of the most significant contributors to the disarray in Singapore’s defense was the animosity between General Bond and Vice Marshal Badminton. This deep-seated conflict permeated the chain of command and had a debilitating effect on cooperation between the Army and Air Force. Their rivalry stymied any attempts at cohesive planning, as both commanders resisted working together on a unified strategy.

The breakdown in communication and coordination meant that instead of working towards a common goal, commanders often had conflicting objectives. This fracture at the highest levels of command trickled down to subordinate commanders, further crippling any chance of unified defense.

Airfield Defense

A Failure of Strategic Location and Protection

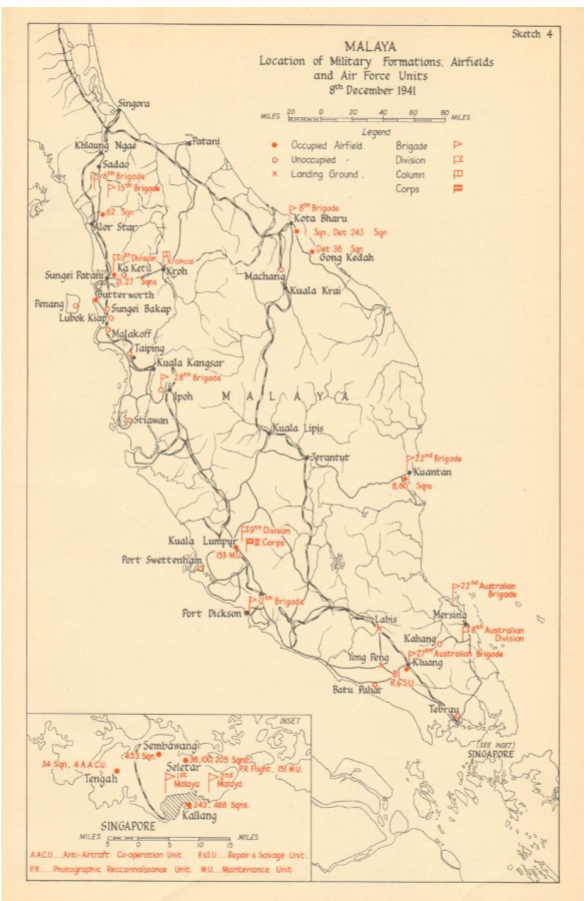

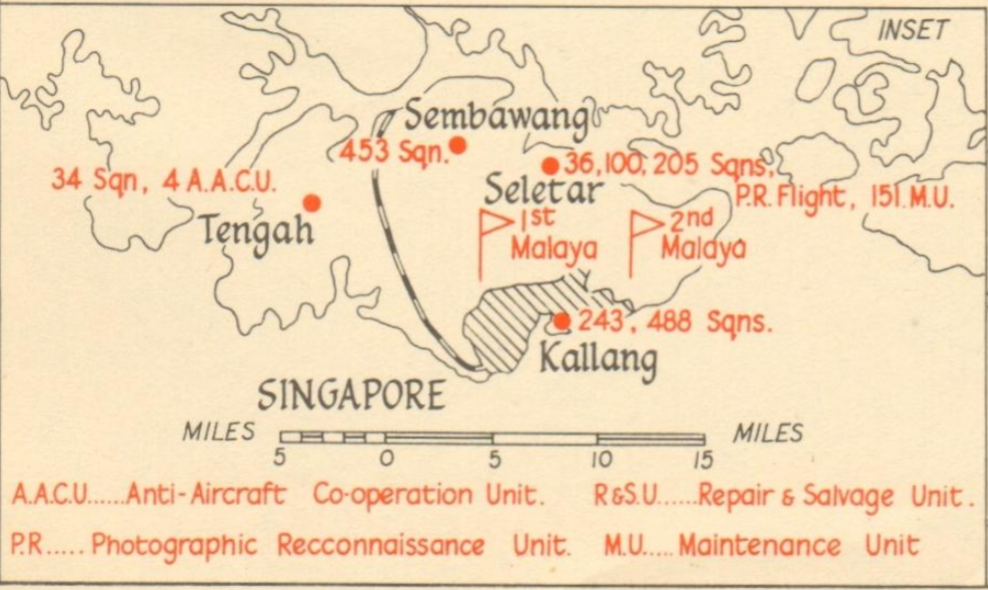

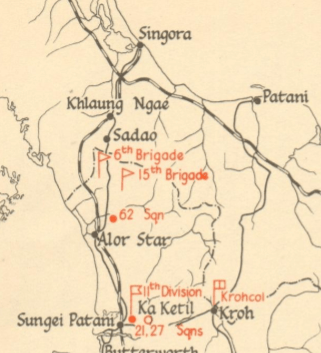

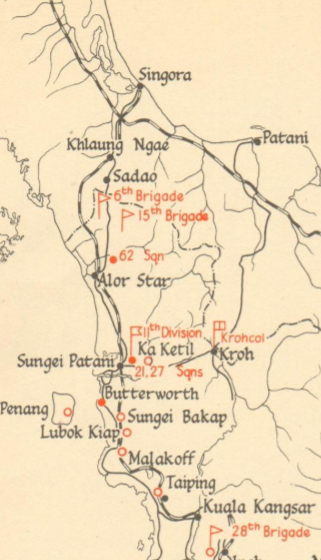

By mid-1941, approximately 22 airfields had been built across Singapore and Malaya, but the siting of these airfields proved disastrous. Instead of choosing locations that could withstand an attack, many of the airfields were vulnerable due to their proximity to the coast and lack of adequate defenses. As a result, these key assets were easily targeted by Japanese air and naval forces.

Even worse, despite a directive that each airfield should be equipped with eight light and eight heavy anti-aircraft guns, by the end of 1941, only 17% of these defensive weapons had actually been deployed. The airfields, already vulnerable, were left without sufficient protection from enemy bombers, exacerbating an already dangerous situation.

A Weak Link

Did You Know?

Underprotected Airfields: Despite plans for robust anti-aircraft defenses, by the end of 1941, only 17% of the necessary guns were in place at Singapore’s airfields.

The Thin Red Line

light Lieutenant Burleson Rath of the Royal Australian Air Force, appointed as Group Defence Officer in mid-1941, conducted an assessment of Singapore’s airfields and found that many were defended using outdated and ineffective tactics. He famously compared the defense strategy to a “thin red line”—a tactic from past conflicts that failed to account for the realities of modern warfare.

Rath was also disturbed by the reliance on a so-called mobile relief column, which was supposed to reinforce airfield garrisons in the event of an emergency. This relief force, however, existed more in theory than in practice. When Major Pill Thompson of the Manchester’s General Staff Office was asked about the force, he admitted that it consisted of just four platoon-sized units with multiple, often conflicting, roles. These units were neither mobile nor sufficient to provide the necessary support during an attack.

Outdated Defense Tactics and a Nonexistent Mobile Relief Force

The Grim Reality at Kluang and Kota Bharu

Inspections in the North

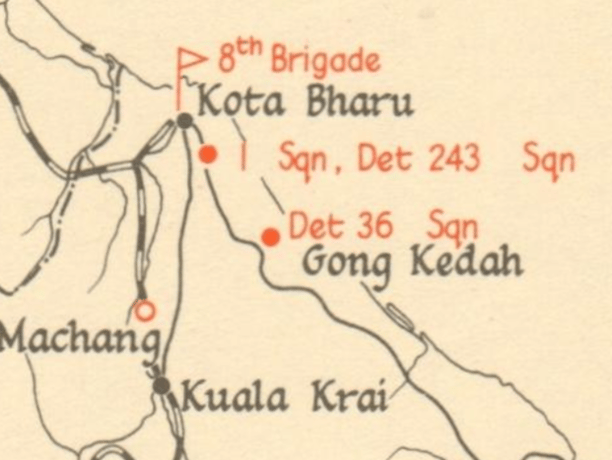

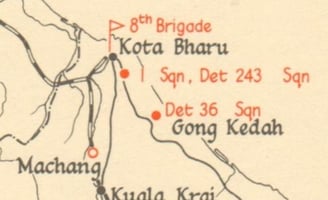

Rath’s tour of northern airfields like Kluang and Kota Bharu was equally troubling. When he visited the northernmost airfield at Kota Bharu, Rath met with Brigadier Quay, responsible for the defense of the airfield. Quay’s resources were stretched thin—his three battalions of infantry were dispersed across a 45-mile frontier and an additional 40 miles of coastline, leaving the airfield critically under-defended.

With only one serviceable field gun available for artillery defense, Quay admitted that enemy destroyers could shell both Kota Bharu and the nearby Gong Kedah airfield from offshore with impunity. Worse still, the proximity of these airfields to the coast made them highly vulnerable to naval bombardment. Despite the dire situation, Quay could offer no guarantees that these airfields could be maintained in the face of an enemy attack.

Did You Know?

Vulnerable to Naval Bombardment: Northern airfields like Kota Bharu and Gong Kedah were perilously close to the coast, allowing Japanese destroyers to potentially shell them from offshore without resistance.

Flawed Intelligence and Leadership

Leadership at the highest levels was as much a problem as the physical defenses. Although intelligence reports had surfaced indicating the capabilities of the Japanese Zero fighter plane, local commanders seemed unaware or dismissive of the threat. In fact, many believed that the outdated Brewster Buffalo, the primary fighter of the Malayan Air Force, could hold its own against the Japanese.

This underestimation of Japanese air power, combined with a refusal to adapt defenses to the modern reality of warfare, placed Singapore in a precarious position. Key leaders like Vice Marshal Badminton clung to outdated assessments, leaving Singapore’s airfields—and ultimately its people—defenseless

The Leadership That Failed to Recognize the Japanese Threat

Conclusion

The internal divisions within Singapore’s leadership, compounded by poor strategic planning and under-defended airfields, meant that by late 1941, the city was a fortress in name only. The failure to anticipate modern warfare tactics, combined with flawed leadership and outdated defense strategies, left Singapore vulnerable to the Japanese assault. It was only a matter of time before these cracks in the defense structure were ruthlessly exploited.

How You Can Help

Donations and Sponsorships: We are seeking corporate sponsorships and donations to fund ongoing restoration projects and educational programs. Your support can make a significant difference in maintaining the quality and impact of the museum.

Volunteer Opportunities: If you have expertise or time to offer, consider volunteering with us. There are many ways to get involved, from artifact restoration to educational outreach.

Spreading the Word: Share this blog and our mission with your network. The more people who know about the JEATH War Museum and its significance, the greater the impact we can achieve together.

The St Andrews Research Team is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Thai-Burma Railway and the memories of those who suffered. We need your support to continue our work. There are several ways you can help:

Join the Cause!

If you or someone you know is interested in supporting this cause, please get in touch.

This is a chance to be part of something truly meaningful and impactful.

Together, We Can Make a Difference!

This is a veteran-run project, and we need your help to make it happen. Stand with us in honoring the legacy of the POWs and ensuring their stories are never forgotten.