You didn’t come this far to stop

The British Army in Malaya and Singapore

during the Interwar Period

Episode 34: The British Army in Malaya and Singapore during the Interwar Period

During the interwar years, British Army units stationed in Malaya and Singapore experienced a life far removed from the battlefield. While they enjoyed certain comforts and privileges, their complacency would later be one of the critical factors contributing to the disaster that unfolded in 1941-1942 during the Japanese invasion. This episode dives into the daily life of British soldiers, the structural and operational challenges faced by the command, and how these factors ultimately undermined the defense of the region.

WW2 HISTORYDESCENT INTO HELLIN THEIR FOOTSTEPS BLOG

Toursofwar.com

8/16/20247 min read

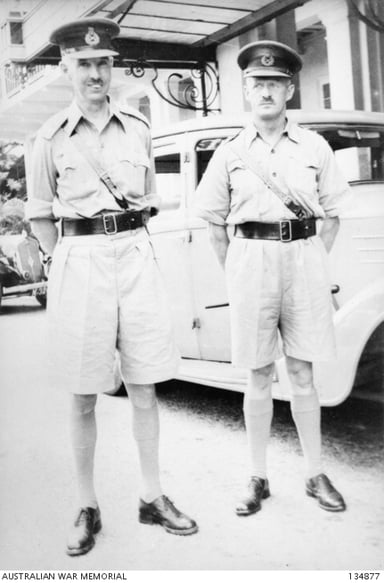

British Officers in Singapore

A Life of Privilege

The Comfortable Life of British Officers

For British officers, garrison service in Singapore and Malaya offered a level of comfort and privilege that was rarely found elsewhere in the empire. Compared to posts in harsher climates or more remote territories, the Far East Garrison provided them with an enviable lifestyle. The officers’ pay stretched far, allowing them access to exclusive clubs and hotels. Sporting facilities were top-tier, and with minimal personal expenditure, officers could afford multiple servants to take care of their every need.

In social terms, British officers in Singapore were akin to the businessmen, planters, and civil service personnel of the colony. The colonial hierarchy allowed them to live a privileged life, largely detached from the realities of impending conflict. Even during the tropical heat of the day, officers found refuge in well-ventilated bungalows or large colonial homes, far removed from the day-to-day hardships their troops experienced.

Regular Leave Diminished the Hardships of Service

Periodic leave to Britain further insulated officers from the full effects of prolonged tropical service. Regular breaks back home made the isolation of Singapore seem less daunting, helping to perpetuate a sense of complacency. The luxurious lifestyle they enjoyed during their deployment, however, did little to prepare them for the looming threat from Japan. In the end, this sense of detachment proved disastrous.

An Improvement in Living Conditions

The Other Ranks

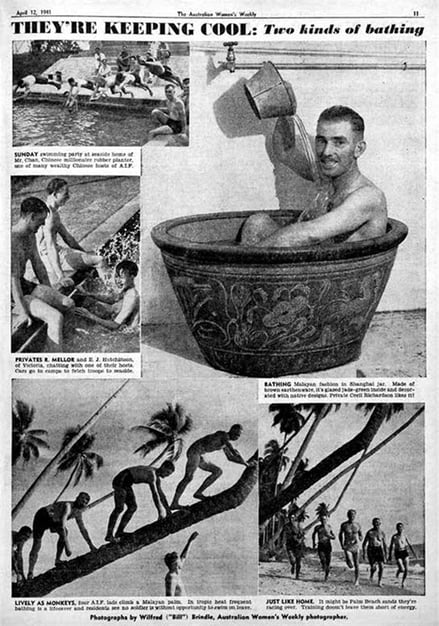

Some aspects of service in Malaya highlighted by The Women's Weekly. (Courtesy Australian Consolidated Press and National Library of Australia)

Privileged in Their Own Right

Although the rank-and-file soldiers did not have access to the same exclusive clubs as their officers, they still enjoyed a quality of life superior to that in Britain or other parts of the British Empire. Barracks in Singapore and Malaya were large and airy, though privacy was limited. Many soldiers took comfort in the improved living standards and social status that came with garrison duty in this region. For many, it was better than the grim realities of industrial Britain, where economic hardship and unemployment were rife.

Leisure and Social Opportunities

Junior servicemen had access to numerous local amenities. Cinemas, bars, amusement parks, and dance halls provided entertainment, while some found more dubious pleasures in the red-light districts of Singapore. The availability of native staff to handle menial tasks further contributed to an elevated sense of status, creating a lifestyle more comfortable than they might have expected elsewhere.

However, this relatively easy existence created a certain lethargy within the ranks. The soldiers were lulled into a false sense of security, unaware of the severe challenges they would soon face.

Did You Know?

The iconic sun helmet or "solar topee" worn by British soldiers in the tropics had been part of their uniform since the Victorian era. Despite its historical significance, by World War II, it was often seen as outdated and impractical for modern warfare, particularly in the dense jungles of Malaya. However, soldiers stationed there continued to wear it during parades and non-combat duties, a symbol of the British Army’s long colonial tradition.

The Loss of Experienced Leadership

The “Milking” Process

Draining the Garrison of Skilled Officers

One of the most significant problems faced by the British Army in Malaya was the so-called “milking” process, where experienced officers and NCOs were transferred out to bolster the forces in Britain and the Middle East. This constant siphoning of leadership drained the garrison of experienced personnel at a time when they were most needed. Even worse, many of these positions were never refilled, leaving critical command roles vacant.

Deterioration of Malaya Command Headquarters

The effects of this were most keenly felt in the Malaya Command headquarters. Although the size of the British forces in the region had grown considerably since 1939, the command structure had not expanded accordingly. Worse still, many of the remaining officers were inexperienced, having been hastily promoted to fill gaps. This left the headquarters understaffed and incapable of effectively managing the rapidly evolving situation as tensions with Japan escalated.

The degradation of command capabilities severely impacted the overall effectiveness of the British defense strategy. While senior commanders such as General Arthur Percival bore the brunt of criticism for the failures in Malaya, it was clear that the "milking" process had robbed the garrison of much-needed expertise at a critical juncture.

A Disjointed Approach

Training Deficiencies

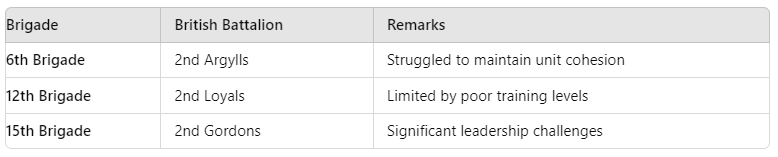

British historian Lionel Wigmore observed that three British battalions (2nd Loyals, 2nd Gordons, and 1st Manchester) were stationed in Singapore, while the 6th, 12th, and 15th Indian Brigades, which could have benefited from their presence, were left without the necessary support. This decision left Indian units in Malaya inadequately led and prepared for the challenges ahead.

Lack of Centralized Training Infrastructure

A major flaw in the British defense preparations was the lack of a centralized, systematic training program. In contrast to the Middle East, where schools and training centers had been established to prepare troops for desert warfare, no such infrastructure existed in Malaya. Training was left to individual brigades and unit commanders, leading to inconsistent and often inadequate preparation across the forces.

Poorly Trained Reinforcements

Indian formations, which arrived in Malaya only partially trained, were expected to adapt quickly to jungle warfare, a completely unfamiliar environment. Similarly, British battalions transferred from China, as well as Australian formations, had little to no experience in the unique conditions of the Malayan jungle. These forces were ill-prepared for the guerrilla-style tactics that the Japanese army would employ, and their training did not prepare them for the close, dense jungle terrain that dominated much of Malaya.

The lack of standardized training, coupled with the climate and terrain, placed the British forces at a severe disadvantage from the start.

Challenges of Leadership

Percival’s Command

The 8th Division’s commander, Major General H Gordon Bennett (right), with Lieutenant General AE Percival, General Officer Commanding Malaya.

Command Limitations and Structural Weakness

General Arthur Percival, commander of the Malaya and Singapore forces, faced a deeply challenging situation. Not only did he inherit a command structure that was weakened by the absence of experienced officers, but many of his senior staff were too junior to have direct access to him. This hindered communication and left critical decisions to those who lacked the authority or experience to make them effectively.

According to historian Clifford Kinvig, Percival was made a scapegoat for the numerous strategic and tactical failings in Malaya, many of which were beyond his control. The British government had consistently neglected to provide sufficient reinforcements or equipment, and the weakening of the command structure left him with limited options. However, Percival's failure to adapt and maximize the limited resources at his disposal also played a significant role in the eventual defeat.

Strategic Missteps

One of Percival's greatest challenges was determining how best to deploy his forces in the face of overwhelming odds. Initially, the British defense plan for Malaya and Singapore relied on naval relief from the Royal Navy's Pacific Fleet. However, after the devastating loss of Force Z, which included the battleships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, the realization set in that the defense of Malaya would depend primarily on ground forces.

Unfortunately, these ground forces were undertrained, under-equipped, and poorly coordinated. Percival was tasked with defending an extensive coastline with insufficient troops and equipment, leaving his forces stretched thin. The eventual collapse of the airfields and the lack of adequate air support compounded his difficulties.

The British battleship HMS Prince of Wales on fire and sinking after being hit by Japanese bombs and torpedoes on 10 December 1941. awm-p01101-001

Conclusion

The Inevitable Collapse

The British Army's defense of Malaya and Singapore was doomed by a combination of complacency, poor preparation, and the failure to recognize the magnitude of the Japanese threat. Although life for British officers and soldiers in the interwar period was comfortable, this sense of privilege and isolation contributed to a false belief that the British presence in the region was unassailable.

The loss of experienced officers through the "milking" process, the lack of centralized training, and the weaknesses in command further exacerbated the situation. General Percival, though criticized for his leadership, was operating within a deeply flawed system, and his efforts to rally the defense were hampered by a lack of resources and strategic support.

In the end, the collapse of British defenses in Malaya and Singapore was as much a failure of preparation as it was a failure of leadership.

How You Can Help

Donations and Sponsorships: We are seeking corporate sponsorships and donations to fund ongoing restoration projects and educational programs. Your support can make a significant difference in maintaining the quality and impact of the museum.

Volunteer Opportunities: If you have expertise or time to offer, consider volunteering with us. There are many ways to get involved, from artifact restoration to educational outreach.

Spreading the Word: Share this blog and our mission with your network. The more people who know about the JEATH War Museum and its significance, the greater the impact we can achieve together.

The St Andrews Research Team is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Thai-Burma Railway and the memories of those who suffered. We need your support to continue our work. There are several ways you can help:

Join the Cause!

If you or someone you know is interested in supporting this cause, please get in touch.

This is a chance to be part of something truly meaningful and impactful.

Together, We Can Make a Difference!

This is a veteran-run project, and we need your help to make it happen. Stand with us in honoring the legacy of the POWs and ensuring their stories are never forgotten.